Roles Converge for Consuper Products Companies & Retailers

By Jim Tompkins &

Bruce Tompkins

May 2013

The Evolution and its Tipping Points

The world of consumer products manufacturers (CPMs) and retailers is evolving right before our eyes. By the time you finish reading this paper, a new concept for selling, delivering or packaging products has likely been developed.

CPM companies (along with footwear and apparel, food and beverage, and even pharmaceutical) can no longer look in the rearview mirror at the past to understand the direction that must be taken for future success.

How can CPM companies really succeed in this evolving landscape and what strategies must they employ?

Clearly, consumers have made a giant leap forward in their buying practices and expectations. Increasingly savvy consumers-as well as growing competition in multichannel spaces-leaves CPM companies at a crossroads, with each path bearing its own risks and rewards.

Sitting at this strategic crossroads, we recognize the key tipping points for CPM companies as:

-

The need to adapt to retailers in the consumerdriven marketplace;

-

Consolidations in the retail industry;

-

Success of companies such as Amazon and eBay;

-

Increased profitability of CPM online sales;

-

The need to respond to technologies used by consumers to buy products;

-

Expanded use of social media by consumers; and

-

Younger consumers and their changing buying habits.

As depicted in Figure 1 below, the path with the right strategy, right technology and right supply chains is the one to follow to gain longterm success in today’s marketplace.

Figure 1: Consumer Products at a Crossroads

As the future unfolds, the lines between CPM companies and retailers are blurring. It is becoming difficult to distinguish one from the other in some instances, and this trend continues to advance at a rapid pace.

CPM companies are functioning more like retailers by selling products directly to consumers or through companies such as Amazon. Similarly, retailers are sourcing more and generating greater revenue from private label products. And all the while, consumers demand more, better, faster, easier and cheaper.

Consider a major CPM company in the bicycle industry as a classic example of a manufacturer using multiple channels to merchandise and sell their products to biking enthusiasts. They sell through retail stores, online through their own website, and through Amazon to reach the maximum number of consumers. Is this bicycle company CPM or retail?

There are also numerous examples of retailers sourcing private label products for sale in their stores and ramping up their online presence to optimize channel coverage. Clearly, the traditional roles of manufacturers and retailers are converging as everyone seeks to make progress with mobile consumers.

How Times Have Changed

CPM companies and retailers are experiencing a dramatic evolution (bordering on revolution) in their roles with consumers. Since the mid20th century, shifting approaches have been the norm – but never more so than today.

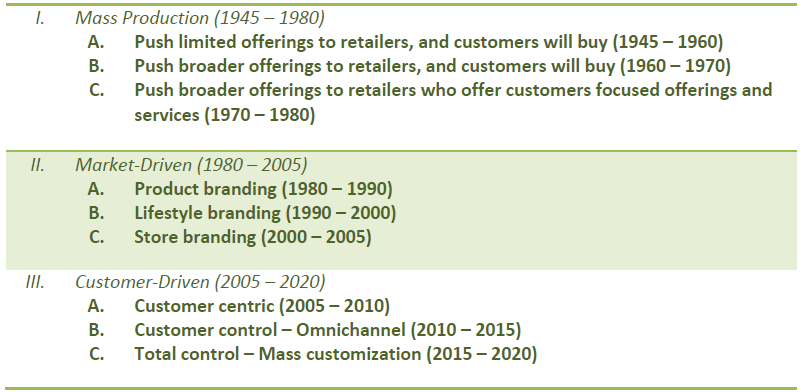

For an indepth perspective, Figure 2 outlines the three evolutionary phases of CPM companies and retailers.

Figure 2: Three Phrases of Evolution for Consumer Product Companies and Retailers

Notice how CPM and retailer roles have changed through the years. But how did these phases unfold?

The story behind Phase I (CPM and mass production) is explored below.

Phase I: 1945 1980

Phase IA (19451960): Retailers such as J.C. Penney, Sears, Montgomery Ward’s, Marshall Fields, Dayton Hudson, Macy’s, Gimbels, Dillard’s, and so forth, had large downtown stores. They worked to convince CPM companies that they should be given the opportunity to sell the CPM companies’ coveted products. They fought for larger allocations and global distributors.

CPM companies pursued high volume, narrow categories with a strong emphasis on increasing capacity to meet demand for products. There was also a focus on improved quality of life for consumers. CPM companies were in control of supply chains and selected which retailers would be allowed to sell their products.

Phase IB (19601970): The mobility of the consumer and a growing suburbia resulted in the opening of suburban markets and regional malls. Big box retailers (Target, Kohl’s, WalMart, and similar) come into existence on a regional basis and started claiming market share.

CPM companies continued to dominate supply chains from product design through to store delivery and sale. As matter of course, CPM companies broadened their offerings to increase sales and respond to various segments of the marketplace.

Phase lC (19701980): CPM companies began to engage retailers more in the planning and logistics of product flow. At this point, they were still the drivers of supply chains and of customers wanting to simplify their lives by accessing more and more products.

Retailers pursued customer services (financing, layaway, returns) and specialization (Toys”R”Us, Circuit City, Best Buy, The Home Depot, TJ Maxx, The Body Shop, and others). At the same time, retailers were starting to think about customer satisfaction and forming strategies to attack certain customer segments.

Phase II: 1980 2005

Phase II involved a shift to marketdriven practices:

Phase IIA (19801990): The CPM companies’ role during this time was marked by a shift to a marketdriven perspective in which supply was adequate, but demand became a limiting factor.

CPM companies needed to differentiate their offerings and provide consumers with a value proposition as to why their products should be selected.

This evolution was first discovered by the CPM companies; therefore, they were the first to begin to market their brands to consumers.

Tide, Chevrolet, CocaCola, Oscar Meyer, Levis, and similar companies launched a huge focus on product branding.

Retailers continued to evolve their role in planning and logistics, but now they found themselves fighting to attract the hot brands. So, although the market had shifted from mass production, the CPM companies still dominated the marketplace from a branding perspective. Specialty retailers, warehouse stores (Sam’s, Costco, BJ’s), apparel (J. Crew, Talbots, Gap) and others responded to specific markets.

Phase llB (19902000): The next logical step after branding individual products was the branding of an image. This image represented a “lifestyle” and allowed the branding of a broad range of products that represented it. Kenneth Cole, Michael Kors, Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger, and similar companies took these brands to a whole new level of value proposition for consumers.

Retailers bought into the concept of lifestyle branding quickly, and thus the competition to attract the best lifestyle brands grew very heated.

The retailers that were successful in attracting the lifestyle brands evolved their relationships with the CPM companies and began to form strategic partnerships.

Phase llC (20002005): As certain retailers captured several prominent brands, the parity between CPM companies and retailers evolved. The CPM companies wanted to be in the “right stores” and the retailers wanted the right “lifestyle brands.” CPM companies and retailers aligned and strengthened their partnerships.

Nordstrom, Bloomingdales, Saks, and similar stores at the high end; J.C. Penney, Sears, Kohl’s, etc., in the midmarket; and WalMart, Target and TJ Maxx at the low end developed clear messages and value propositions for consumers.

This store branding further evolved the shared supply chain responsibilities of CPM companies and retailers.

Phase III: 2005 Ongoing

The next period is the customerfocused era (Phase III) that we are still experiencing today:

Phase lllA (20052010): This involved an evolution of the marketdriven phase in which the consumer wrestled control away from CPM companies and retailers. As a rule, the consumer defined the experience and the retailers and CPM companies responded. Supply chains evolved from a push to a pull.

Retailers began to change their thinking and focused on listening to their target customers and responding to their desires, and then telling CPM companies what they wanted. Retailers gained greater power over CPM companies because they were closer to customers. Category killers (Barnes & Noble, Blockbuster, Linens n’ Things, The Home Depot, Sam’s Club, and related retailers) catered to their targeted customers’ desires, and thus they thrived.

Phase lllB (20102015): CPM companies begin to wonder about their roles. They see retailers moving to private label and are forced to begin offering their products for sale online. The boundary between CPM companies and retailers becomes markedly blurred. CPM companies are becoming more like retailers, and retailers are becoming more like CPM companies.

Then, the success of Amazon.com changes the whole game. Retailers are forced into providing great prices, awesome selection, bestinclass convenience and personalized experience while offering the consumer accessibility at any time, in any place, and in multiple ways. Instore retailers must go online and offer products that allow them to control their supply chains.

Phase lllC (20152020): As customers take total control of satisfying their own product needs, CPM companies and retailers are pushed to take control of their supply chains in order to fulfill the needs of their target customers. The result: There will be very little difference between CPM companies and retailers, since they both follow the model of DesignPlanBuyMake MoveStoreSell. Retailers and CPM companies will continue to transform their supply chains into finelytuned vehicles that allow them to deliver their business strategies to the marketplace. But accomplishing this feat will mean taking total control of supply chains and offering customers the opportunity to customize their products, convenience and experience in accordance to their own expectations about buying experiences. In short, customers will be in control and pull product through supply chains.

The Pace of Change is NeverEnding

What started out as a time of minor changes in mass production has now transformed into sweeping changes in customer expectations for every product that moves through supply chains today. The phases and timeline presented above clearly demonstrate how the pace of change has accelerated.

Obviously, technology has played a key role in getting us from the world of mass production to marketdriven to customerdriven. We fully expect that the future pace of change will continue to accelerate – probably faster than we can predict.

To be successful in this changing marketplace, CPM companies and retailers will need to focus on delivering value to customers at a higher level than they have ever done before, along with growing more innovative in their approach to supply chains.

To gain a fuller perspective on the changes that have occurred over time, Tompkins has organized CPM and retail companies’ responsibilities by phase and supply chain process. The perspective of CPM companies is given in Figure 3, and the perspective of retail companies is shown in Figure 4.

![]()

Figure 3: CPM Companies’ Responsibilities by Phase and in Each Supply Chain Process

![]()

Figure 4: Retail Companies’ Responsibilities by Phase and in Each Supply Chain Process

Dissecting the above tables provides interesting perspectives on what was actually occurring during the various evolutionary phases for CPM companies and retailers.

In Phases IA, IB, IC, IIA and IIB, CPM companies and retailers were working together and jointly achieved a total score of 10. But from IIC forward in time, the sum of the responsibility values for CPM companies and retailers has been greater than 10. This indicates a blurring of the boundaries between CPM companies and retailers.

As previously noted, CPM companies are becoming more like retailers and retailers are becoming more like CPM companies.

CPM companies totally dominated the relationship with retailers through Phase IIC. Beginning with Phase IIIC, retailers were selling more private label and CPM companies became less important to them.

Of course, CPM companies noticed this trend and began expanding by opening their own stores and/or selling online in various ways.

Note that there are several dynamics taking place in the “Plan” column of the tables. During Phase IA, the supply chain is a push system. CPM companies do internal S&OP and push products to retailers with little or no input from retailers.

As the phases progress into IB and through IIC, retailers’ roles in planning are increased in helping CPM companies plan the volume of product that will be pushed through supply chains.

However, as discounting of unsold goods continues to grow, supply chains become more and more pull oriented. Particularly in Phases IIIB and IIIC, supply chains for CPM companies and retailers become increasingly pull oriented – and thus the evolution to demanddriven supply chains indicated in Phase IIIC.

In fact, as we approach 2020, the gap between CPM companies and retailers will close even further, and both will be dominated by demanddriven, customer driven supply chains.

The “Move” and “Store” columns of the table also tell an interesting story. Through Phase IIC, CPM companies and the retailers’ efforts are in concert.

But over time, retailers take greater control of transportation and distribution of their products. Of course, starting in Phase IIIA, both CPM companies and retailers increase their control of “Move” and “Store” supply chain processes.

Tompkins International’s inclusion of the “Sell” process provides a new perspective on CPM and retail supply chains. Retailers have always been the “Sell” function, but since Phase IIIA, CPM companies have also been involved with selling at an ever increasing pace.

The process of “Design” must also be added to the mega processes of supply chains, since retailers have taken on a growing role in the design of the products they market and sell.

Strategic Directions

CPM companies are facing difficult decisions about their future identities. They must decide how to satisfy customers and simultaneously maintain relationships with retailers, as well as potentially a host of other new enterprises such as Amazon.

Any future business decisions must also be decisions about supply chains. And supply chains built to solely support retail stores are far different from supply chains that facilitate online sales and markets and also support stores.

This is exacerbated by the challenges of meeting consumer expectations on price, selection, delivery and convenience (which retailers are experiencing as well).

What options do CPM companies have to grow sales in this omnichannel marketplace? They could:

-

Continue to sell to retailers and support their challenging requirements;

-

Sell products online using their own web presence;

-

Set up their own branded retail stores;

-

Sell through outlet stores;

-

Utilize Amazon and other pure online sales channels;

-

Sell through multisided platforms such eBay; or

-

Some combination of all the above.

Identifying the correct business strategy for a particular company is a huge challenge. What may be successful for some products that a company offers may not work well for others. The strategy must take into account the many factors that affect how consumers interact with the company and how they prefer to view and purchase products.

In addition, the strategy may need to be more about providing consumers with information so that the best purchasing decisions can be made instore. CPM companies must weigh all the alternatives and decide which options they can fully support and successfully execute.

Overall, the business strategies that identify how CPM companies will go to market are the drivers of supply chains. Therefore, each company must determine business strategy first, and then the required capabilities of the supply chain can be identified and implemented to achieve this strategy.

Too often, supply chain capabilities are used to make the decision about which business strategy to pursue. The path to success is strategy before structure-not structure driving strategy.

Charting Your Course

Today more than ever, a sound business strategy is essential in order to decide how to optimize sales and profits. Once the approach to the market is determined, the difficult job of matching supply chains and technologies to the approach can be undertaken by company leaders.

The business strategy requires continuous monitoring to ensure that it yields the expected results and adjustments to keep the organization on track. Moreover, the progress of supply chain transformation must be monitored with urgency in order to keep customers’ needs in focus.

Successful CPM companies understand the marketplace transition that has occurred and are meeting the challenges and expectations of today’s consumers. To move beyond this shared crossroads, CPMs and retailers must have meaningful “conversations” with consumers and build demanddriven supply chains that respond in realtime.

About Tompkins International

Tompkins International transforms supply chains to help create value for all organizations. For more than 35 years, Tompkins has provided endtoend solutions on a global scale, helping clients align business and supply chain strategies through operations planning, design and implementation. The company delivers leadingedge business and supply chain solutions by optimizing the Mega Processes of PLANBUYMAKEMOVESTORESELL. Tompkins supports clients in achieving profitable growth in all areas of global supply chain and market growth strategy, organization, operations, process improvement, technology implementation, material handling integration, and benchmarking and best practices. Headquartered in Raleigh, NC, USA, Tompkins has offices throughout North America and in Europe and Asia. For more information, visit www.tompkinsinc.com.

Contact Us

Email Tompkins International at info@tompkinsinc.com.

This paper is the result of Tompkins International’s research of public information. There is no information presented that comes from any proprietary source. Tompkins International does not discuss information about their clients unless that information has been published.